The Missing Chapter

The 731st USAF Night Intruders Over Korea

(The book chapter entitled: In The Begining should have been “Our Proud Heritage”)

We conducted training sessions in every conceivable place — from a condemned WWII barracks at Van Nuys Airport, to a church fellowship hall in Covina.

Our intended role in the Air Force Order of Battle was as uncertain to us as next month’s weather forecast.

While the Pentagon Planners made up their minds, we grumbled and griped as we successively studied charts, statistics and tactics on the C-47, B-25, AT-11and eventually the B-29.

As the majority of our WWII experience had been in B-17s and B-24s, the transition into Superforts made a lot of sense. At least it seemed a realistic and practical course to pursue. There were still uncertainties, however. We had no airplanes, and no airfield to put them on. Would we get paid, and when? Would there be promotions, and when? Lots of questions, but no answers.

Nobody seemed to have a handle on the “Big Picture.” Our early pride and enthusiasm was being severely wounded by the “water-drip” torture of the continuing frustration. Some people decided they had better things to do after all, and dropped by the wayside. The “diehards” hung on. The new-found esprit de corps, and the rekindled comaraderie of a not yet forgotten era breathed new life into our struggle for reorganization.

After what we had already experienced, the announcement that another change was in the wind had little effect on us other than resigned acceptance. Even the assurance that the indecision and vacillation were over — that we would become a Douglas B-26 light bomber unit — generated only wary exultation. But this time it was for real. The seed of conception of the “night-intruders”, though far from being “immaculate”, had been sown.

Whether just by an odd quirk of predestination, or by someone’s astute analysis of military intelligence, the decision to equip the 452nd with B-26s rather than B-29s couldn’t have been more timely and appropriate. Somebody must have foreseen the eventual need for a whole lot more B-26s with trained air crews, than those comprising the two under-strength Regular Air Force squadrons of the Japan-based 3rd Bomb Group.

Somebody must have known something that the general public — including us –didn’t know. But we were now into 1948, and the Korean debacle was still over two years away.

In any event, the die was cast, and by mid-summer the 452nd Bomb Wing (Light) had hung out their shingle at the Long Beach, California Airport.

Instead of the intense “pressure cooker” of seven months training imposed on our WWII progenitors before they met their enemy, we proceeded more or less leisurely through weekend after weekend of training — blissfully unaware of what fate had in store for us.

Among the troops, at least, there was not the remotest concern about the possibility of another conflict. We were too caught up in the excitement of getting back into our old “pinks and greens”-tight-fitting and reeking of mothballs; readjusting the crush of “fifty-mission” hats, and enjoying the reprieve from the strange and unaccountable boredom of being a “civilian” again.

Gradually and painstakingly, the compels machinery that would transform the nucleus of a few dozen eager and dedicated men into a fully operational and finely tuned fighting machine, shifted into high gear.

Earlier question marks were erased with the promise of full pay and allowances, with flight pay and an extra bonus of promotion to the next highest rank for all eligible personnel. We began to train one weekend a month from Friday evening to Sunday evening, with a two week active duty tour to occur within a year. Pilots and crew chiefs flew by C-47 to Hill AF Base at Ogden, Utah, to pick up our de-mothballed “Invaders.” Hundreds of personnel–from clerks and cooks, to pilots and propeller specialists–were recruited through a concerted radio, newspaper and mail campaign. The long-dormant facilities at Long Beach were soon vibrant and pulsating to the rhythm of clacking typewriters, clanging tools and roaring Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines.

Less than a year later, in May 1950, the “week-end warriors” assembled for their promised tour of active duty. For fifteen cays classrooms, cockpits, offices and hangars hummed with activity; serious men training for a serious mission that they had no inkling of soon being called upon to perform.

But unfortunately, the decision makers who had somehow foreseen the need for an augmented light bomber force, had not anticipated needing a night attack unit. So on 25 June 1950, when the Communists raised the curtan on Act I of their South Korean invasion, the men of the 452nd were almost, but not quite, prepared for their roles in the forthcoming drama.

We didn’t have long to wait. Our invitations to attend a full-scale dress rehearsal at George AF Base, Victorville, California, came by telegram dated 1 August, 1950. The honeymoon was over. Effective 10 August, the 452nd was back on active duty. Only this time there would be no more “leisurely” training week-ends — the tour was for twenty-one months.

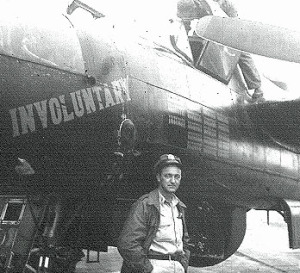

To say that there was a state of confusion at “George” as the troops swarmed in that red-letter day in August, would have been the grand daddy of understatements. It was more akin to pandemonium. But gradually, as the shock of the unexpected and “involuntary” recall wore off, and the disappointing, discouraging effects of: leaving homes and loved ones; businesses; studies and careers; had run their course, we began to create order out of chaos.

While the Combat Support Group was submerged in the morass of paper work and physical labor involved in the mobilization and preparation for deployment of the Wing, lock-stock-and-barrel to Japan; and while the other tactical squadrons resumed the daylight training conducted during the June active duty tour, it was virtually back to “square one” for the 731st. Having received the dubious honor of becoming the 5th Air Force’s first officially designated “night-attack” bomber squadron, we had just sixty days–or more accurately, nights–, to learn how to fly, navigate, bomb, rocket and strafe at low-level, in pitch dark, over the Mojave Desert.

The reincarnation of the 731st Bomb Squadron was consummated. Except for our twin-engine B-26 “Invaders” in lieu of the B-17 “Flying Forts”, the scenario was essentially the same as in WWII. The old “pressure cooker” was boiling on the front burner. We had a deadline to meet. We would soon be on center stage–playing our parts in the tragedy of a war that was erroneously and unforgivably–though perhaps technically correctly–referred to as a “police action”, but on which the impact of our presence would long endure.

But the 5th Air Force and 3rd Bomb Group’s calls for help were urgent. The North Korean Reds had become a tenacious and formidable force to deal with. In response to the emergency, four 731st air crews double-timed through a modified training schedule, flew their aircraft to Japan, and were in the thick of the action by the middle of September, 1950.

Although it would take almost two more months for the remaining troops and aircraft to join them, our initial calling cards to the “bad guys” had been superbly and insuperably delivered.

Master Navigator Chester L. Blunk, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF (Ret.)

Born at Denver, Colorado, 27 May 1920. Enlisted Army Air Corps, August 1942. Commissioned 2nd Lieutenant, Bombardier, at San Angelo, Texas, July 1944. Flew 14 missions with the 459th bomb Group (B-24’s), 15th Air Force, in Italy during WWII. Separated from service in November 1945. Recalled to active duty in August 1950 with 452nd Bomb Wing at Long Beach, California.

Assigned to 731st Bomb Squadron, which was detached from the 452nd Bomb Wing and made part of the 3rd Bomb Group at Iwakuni, Japan. Flew 58 missions during the Korean Campaign.

Decorations held: Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters, Air Force commendation Medal with on Oak Leaf Cluster, Purple Heart, Presidential Unit Citation with two Oak Leaf clusters, Korean Presidential Unit Citation, Air Force Outstanding Unit Citation, European Theater Campaign Ribbon with five Battle Stars.

Held Master Navigator rating with over 4,000 hours total flying time: 1,200 hours in the B-26; 1,500 hours in the B-47; with the balance in various aircraft including the B-24, B-17, B-52, C-47 and KC-135.

Instructed low-level, night-intruder tactics and Shoran bombing in the B-26 at Langley Field, Virginia, 1951-54. Graduated Navigation Upgrading School at Mather Field, California, in September 1955. Assigned Strategic Air Command from 1955 until retirement in July 1969.